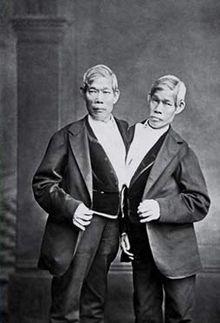

Conjoined Twins

Chang and Eng Bunker. Born 1811. Thailand.

One might wonder how conjoined twins manage to survive – physiologically, mentally, and emotionally – after surgical separation. While some sets of conjoined twins, for medical reasons, cannot be separated, as in the somewhat famous case of Brittany and Abby Hensel, since 1987 several have been successfully separated. In some cases, conjoined twins, who are old enough to make thoughtful choices, have refused to be separated. Lupita and Carmen Andrade, who were expected to live only three days after they were born, not only defied the odds, but are now living together, literally. Both refused the option to be separated. According to the Deccan Chronicle, the twins say “it would be like cutting them in half.”

The decision to surgically separate conjoined twins is not one to be taken lightly. Inevitably, ethics comes into play. The most urgent question of all: What if one twin must be sacrificed? Do we allow one twin to die to save the other? Which twin’s life matters more? The questions are endless, questions I can’t imagine having to face if I were the parent of conjoined twins.

You might be wondering why I’m writing about conjoined twins, why I’m sharing with you this extremely rare and mind-blowing phenomenon. I’m sharing all this with you because I cared for a set of conjoined twins as a neonatal intensive care nurse. Though decades have passed since I held all *fourteen pounds of sweetness in my arms, fed them, changed their diapers, and held my breath as I waited for the then eight-month-old twins to come out of the hours-long surgery, I’m still awestruck. So what does a writer do with all that awe? Naturally, she writes about it. Which is exactly what I have done in my essay, “After,” published today at Intima, a literary Journal dedicated to promoting the theory and practice of Narrative Medicine. Created in 2010 by graduate students in the Master of Science program in Narrative Medicine at Columbia University, Intima has featured writers in the literary and medical fields from around the world.

Thank you for reading “After,” and feel free to follow-up with thoughts, questions, and, of course, your own awestruck moments.

*fourteen pounds is a guesstimate.

Read More

Recent Comments