Review of Marianne Leone’s Memoir Jessie

Born ten weeks premature, Jesse Cooper suffered a brain hemorrhage, and survived – with cerebral palsy. In 2005, at age seventeen, he died.

During the course of my twenty-year career as a pediatric and neonatal intensive care nurse, I cared for thousands of babies and children, many who had cerebral palsy. I provided the best care possible – heeded their cries, exercised their rigid limbs, and carefully fed them pureed foods so they wouldn’t choke. But it was impossible for me to know what it was like to be a mother of a child with cerebral palsy, or any of the ill children I cared for.

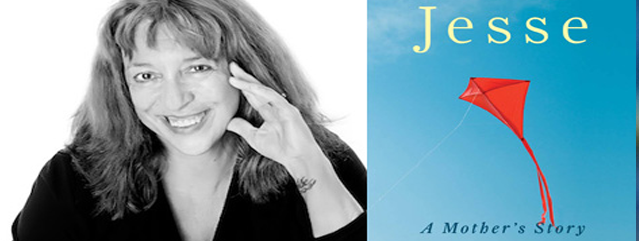

But actress Marianne Leone knows. In her memoir, Jesse, Leone writes with stark prose, sharing with us her “mask of red rage,” and her “fuck-you double slather of red lipstick,” as she, and her actor-husband Chris Cooper, work tirelessly to navigate the hairpin turns of their lives caring for a child with cerebral palsy (185, 189). She lures us along in their trek, from Jesse’s endless days in the neonatal intensive care unit, through their frustrating odyssey in search of physical, occupational, and speech therapists who would treat Jesse with dignity, and their fevered commitment to convince the school system within their community to integrate Jesse into classes with what Leone calls “able-bodied” students. Leone reminds us that “Jessie wasn’t a CP kid first, and a kid second (57).”

Jesse is more than a mere telling of the speed bumps Leone and her family encountered along the way. It is a story of perseverance, and idiosyncratic family coping mechanisms in the face of Sisyphean challenges. It hurtles the reader into a better awareness of what it means to be a quadriplegic, and non-verbal – which does not equate with being an “idiot (31).” Leone’s memoir is a must-read for families, health care professionals, teachers – all of us – who are on a quest to do what is right for our children, whether or not they are disabled.

Jesse speaks to the human condition – in this case, internal conflict – and the human being in us: Even long after the death of her son, Leone admits she’d rather “stay inside and be alone (248).” But she also knows, in order to still feel connected with her son, she must reach out and talk to other mothers with “babies like Jesse (248).”

Jesse himself tugs at the human being in us. His humor, non-judgmental approach to others, and endurance – he was an honor roll student, and windsurfed and wrote poetry – impels us to take a long, hard look at ourselves and ask, “Who am I? Am I aware of what is happening around me? How do I treat others? How do I want to be treated? What meaningful contributions am I making to others? What if I were a quadriplegic and non-verbal?”

In an autobiography Jesse wrote in sixth grade, he says:

“The most important lesson I can teach/is to see people for what they can do/ and not for what they cannot do (82).”

Recent Comments